Designer vs. Artist

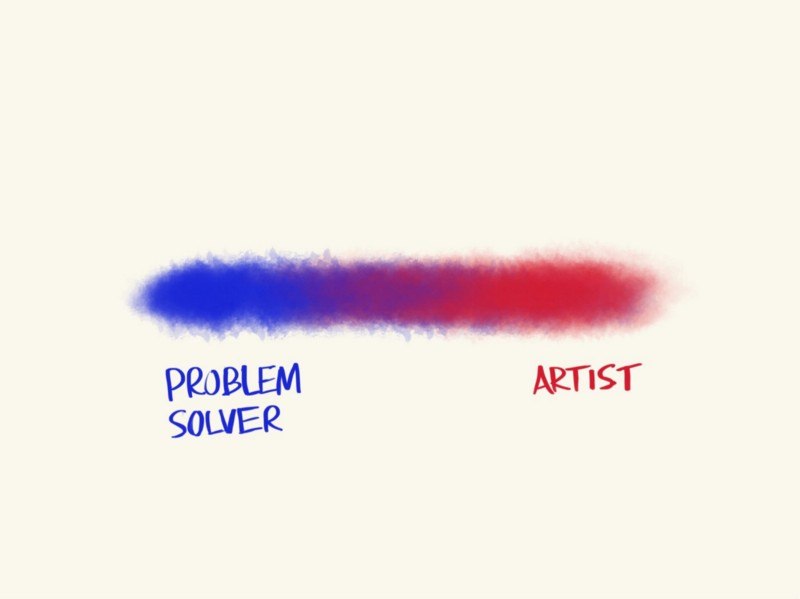

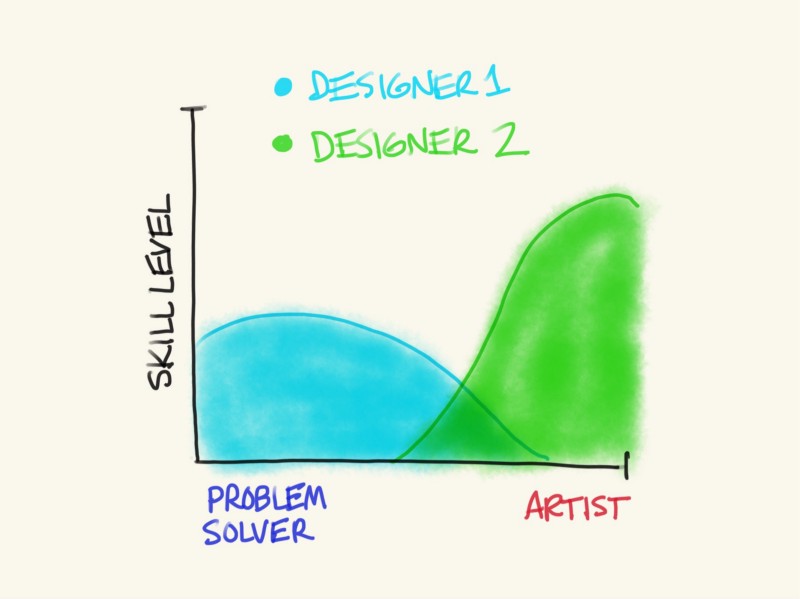

The profession of an artist and designer are different and also inherently linked. Generally speaking, an artist does not need to have clear objectives when setting out to create while designers typically have a measured set of goals for their work. However, the design profession is a very broad one. It’s too simplistic to say design can be classified as art or that it cannot. The reality is that each designer occupies a range between artist and problem-solver. Let’s call it the Design Spectrum.

(See graphic above)

The Design Spectrum

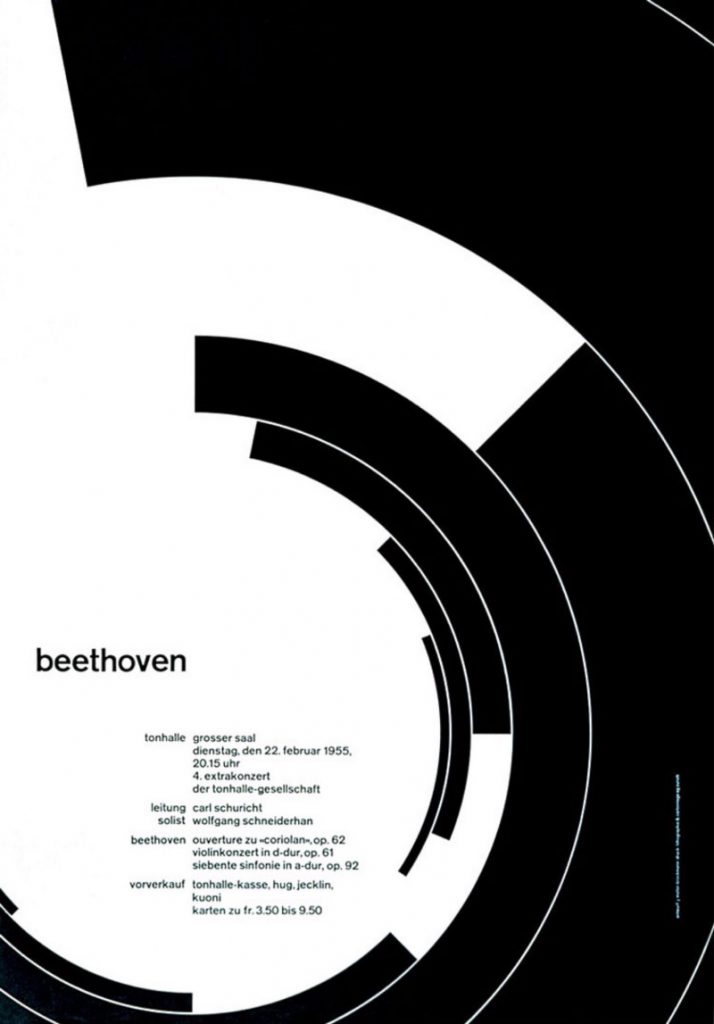

On one end of the spectrum, the designer is strictly a problem-solver. Masters of the International Style of graphic design, such as Jan Tschichold and Josef Müeler-Brockmann, attempted to standardize the craft of graphic design by establishing order and best practices. Through clear, clean and precise typography and layout, these designers mastered a form of communication that still feels relevant today. While their work is truly timeless, it is also mostly devoid of personal expression.

Josef Müeler-Brockmann

In a famous 1972 interview, Charles Eames defined design as “A plan for arranging elements to accomplish a particular purpose.” Very matter-of-factly, Eames explains that design depends largely on constraints. He said it’s a designer’s job to work within these constraints to find the best possible solution. However, when asked whether design is an expression of art, Eames leaves the door open:

“I would rather say (design) is an expression of purpose. It may, if it is good enough, later be judged as art.”

Eames experimented with new materials and processes of production to produce furniture that was more functional, economical and beautiful. The innovation, attention to detail and purity of form showed that he was working at a very high level and pushing the craft forward. So much so, many today do indeed consider his designs works of art.

Charles Eames

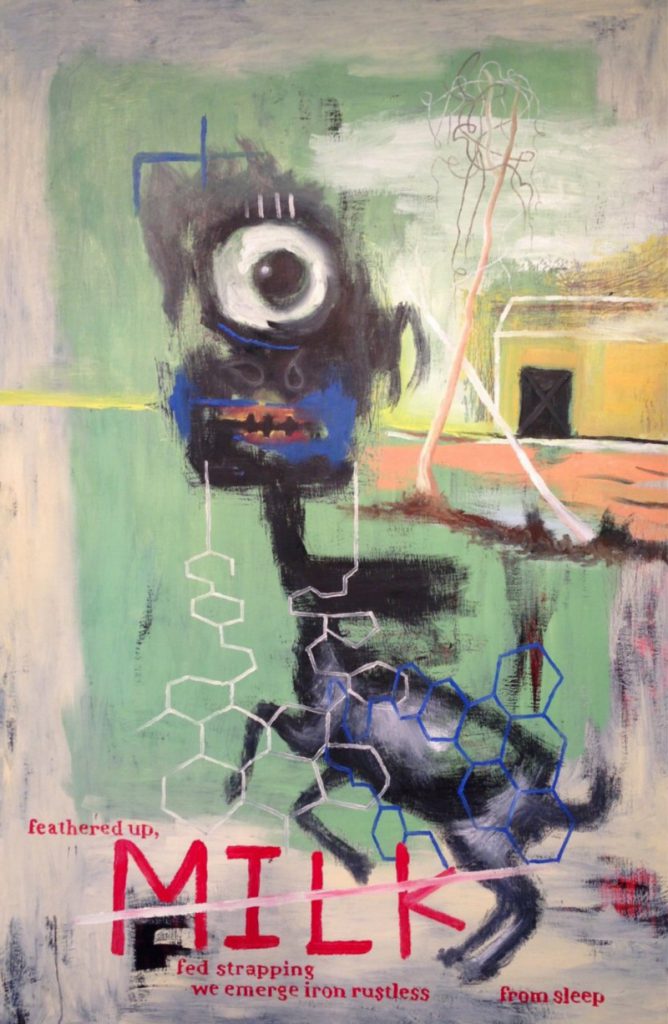

On the other end of the spectrum, there is little separation between the work of a designer and the work of an artist. Take designer Elliott Earls, for instance. His work is unconventional in the most intentional way. Earls rejects the commercial tendencies of design to achieve something far more provocative and original. Whereas Eames defined design as a solution to a problem, Earls’ work raises more questions than answers.

Elliott Earls

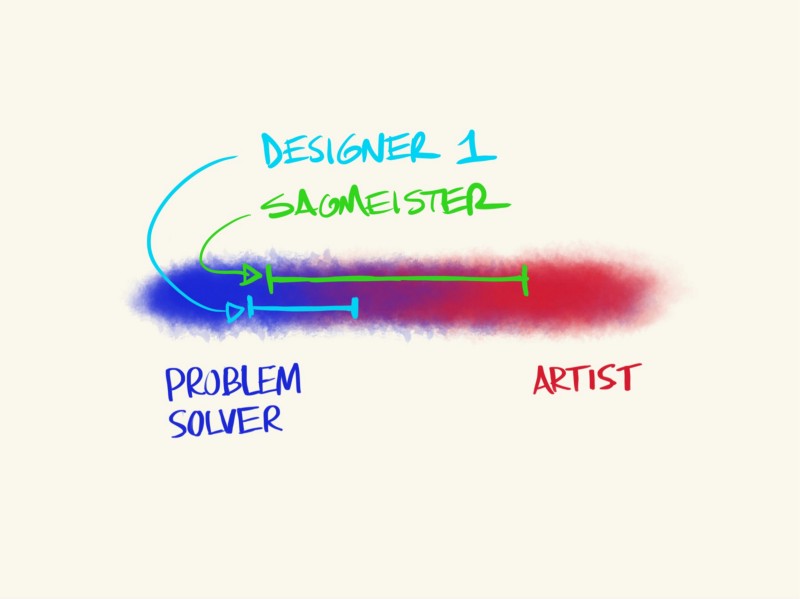

All designers are not created equal. The range of the spectrum that each designer occupies can vary. Some stretch far into both sides of the spectrum — like Stefan Sagmeister.

Sagmeister often blends two ends of the spectrum by using untraditional methods to solve traditional problems.

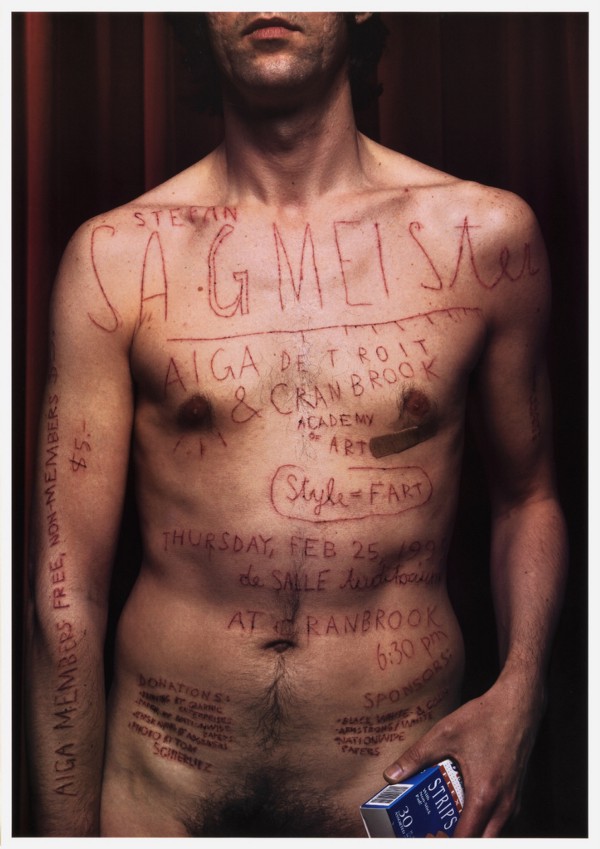

Stefan Sagmeister

Have a look at this poster from 1999 for an AIGA event at Cranbrook Academy of Art (which happens to be where Elliott Earls was appointed Designer-in-Residence in 2001). Sagmeister’s poster for the event is of a standard size and communicates all of the information through typography, but that’s where traditional ends. The type was actually carved into Sagmeister’s skin by his intern. By doing so, Sagmeister conveys the personal nature of design work, and the pain we often experience while creating it.

This is not to say that a designer who primarily operates within a narrow space of the spectrum is inherently lesser. The 2D spectrum I’ve included above doesn’t tell the whole story. A more accurate one would be a 3D visualization where depth of skill, knowledge, experience and mastery are represented:

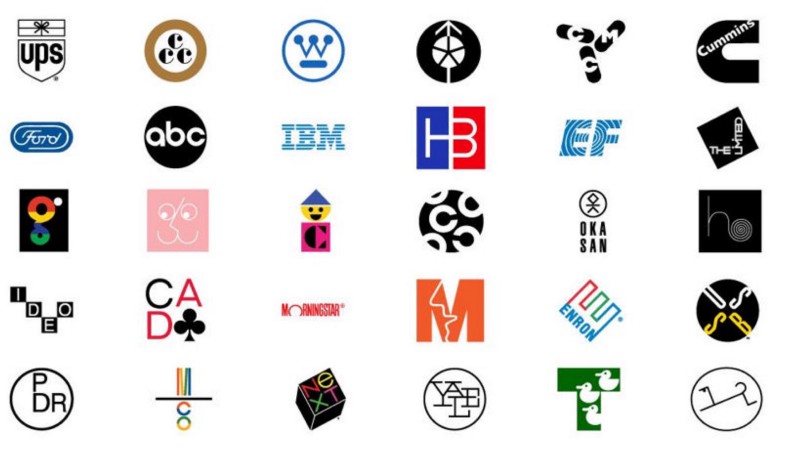

While Paul Rand might be thought of as primarily a problem-solver, his mastery of his field was unprecedented. He defined the whole landscape of modern corporate identity design.

Paul Rand

Although Elliott Earls has publicly declared a deep disdain for Rand’s work, my guess would be that Rand would feel the same way about Earls’ for failing to quickly and clearly communicate its purpose. Personally, I think we need them both.

As designers, we should look to heighten our skill through learning and experience. Remember—our space on the spectrum is not fixed. We can always work to stretch our range. And when work extends beyond our comfort zone, we must not dismiss it. We can all stand to learn from someone who operates differently than we do, better than we ever could.